We will be celebrating Candlemas for the first time this evening.

The celebration of the Purification of Mary is known to have been celebrated from the times of persecution, for we see its celebration in the Church at Jerusalem in the time of Constantine’s conversion. At first celebrated 40 days after Epiphany, when Epiphany celebrated the Nativity of Our Lord, the Feast settled on February 2 after the Feast of the Nativity was established on December 25. In the Eastern Church it was called Hypapante tou Kyriou, the meeting of the Lord and His mother with Simeon and Anna.

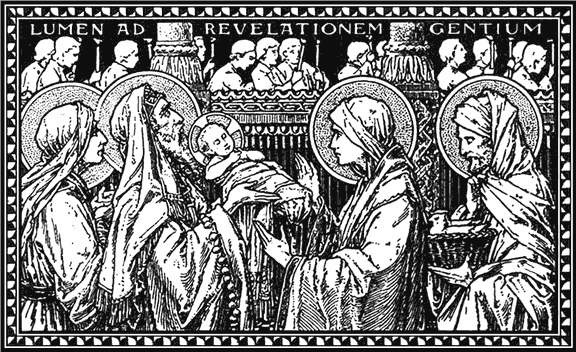

During the Feast today, the priest offers five prescribed orations before he blesses beeswax candles by sprinkling and incensing. The candles are then distributed while the Canticle of Simeon is sung with the antiphon “Lumen ad revelationem gentium et gloriam plebis tuæ Israel,” “A Light to the revelation of the Gentiles, and the glory of thy people Israel,” repeated after every verse. Then follows the procession, and at which all the partakers carry lighted candles in their hands, the choir sings the antiphon “Adorna thalamum tuum, Sion”, composed by St. John of Damascus.

The solemn procession represents the entry of Christ, the Light of the World, into the Temple.

It has been a blessing rediscovering the ancient traditions of the Church. I am grateful every day that the Lord led us home.