Scott has a great post on hackberries over at The Grow Network:

I’ve been asked a number of strange and interesting foraging questions. Usually, it’s something along the lines of, “What plant is this?” (I find plant-identification questions to be the most reasonable and ridiculous, all at once. On the one hand, identifying plants is a big part of what I do. On the other hand, there are close to 400 million species of plants in the world, so I’ve given plenty of shrugs in answer to that question.) But my favorite question might have been when someone asked me if there was a foraging equivalent to Grape-Nuts cereal. It was so absurdly specific and random. And best of all, I knew the perfect answer: hackberries.

Getting to Know Your Local Hackberry

Hackberry is the common name used for trees in the Celtis genus. They grow throughout the warmer areas of the Northern Hemisphere—including throughout the United States, southern Europe, and Mexico, and in parts of Canada and Asia. They can also be found in northern and central South America and in southern to central Africa. I’ve heard no reports of hackberries in Australia, but they’ve traveled around so well, I’d be surprised if a few hadn’t found their way on over.

Hackberry trees prefer to grow near water sources, though I’ve seen plenty in relatively dry places. They compete well with other trees and are easily spread by hungry birds. If you live in any of the places mentioned above, chances are pretty good that you have hackberries nearby.

Most trees in this genus produce an edible fruit, though you may want to double-check with a wild plant expert in your area just to be sure. (Safety first, right?) The predominant species in my area, Celtis laevigata, is also called the sugarberry tree. This is an apt name. The fruits are sweet, but the pulp is about the thickness of tissue paper. Thankfully the seed is also edible. More on that in a moment.

Identifying the Hackberry

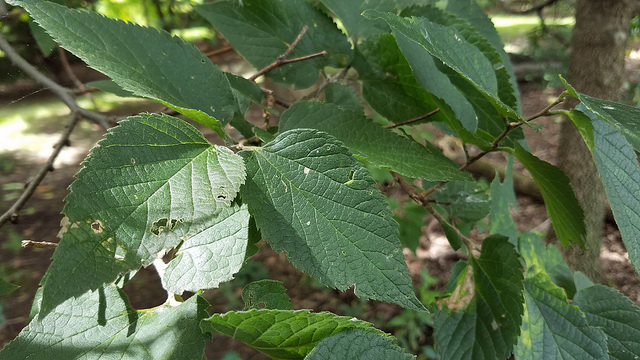

The leaves are alternate, longer than they are wide, and have asymmetrical bases. Leaf galls are common enough that they can practically be used as an identifying feature.

The bark is grey and smooth, but punctuated randomly and frequently by warts. These warts have a consistency similar to cork and are one of the key identification features of the tree. At least one species has thorns.

Depending on the species, hackberry trees can grow quite tall, which makes harvesting the fruit a challenge. I may be imagining it, but I always seem to spy more berries up in the higher branches than in the lower ones. I usually back my truck up underneath a tree and stand in the bed to harvest them. I also know of a couple of trees that grow together on a steep hill, making one side of the tree very accessible. Geography allowing, this may be a strategy you can utilize. A little judicious pruning could also help to shape a tree, if you start it young enough.

The fruit is small, about the size of a pencil eraser. It will take you a while to gather any sizeable quantity. The color ranges from a reddish-orange to a purple-red. But keep in mind that I don’t have the most reliable color vision, so your results may vary slightly. As stated above, the fruit is mostly seed. The seed is edible and you can crush it with your teeth . . . unless a dentist is reading this, in which case I meant to say, “Never crush the seed with your teeth.” The skin is crunchy with a very thin, sweet pulp. Think of them as a wildcrafted version of a Peanut M&M.

Read the rest of the post here. There’s a lot more.

I had multiple large hackberry trees in my Tennessee yard. The fruit were lackluster, rather like a dried coating of date skin over buckshot, but they tasted nice. I had no idea there were better types. In Tennessee, people often considered them a “trash” tree. I thought they made nice shade trees, though, and the bark was interesting.

Another thing I liked about my hackberry trees was the leaves they produced. They composted readily, and at night in the fall I could actually hear the worms gnawing at the layer of leaves beneath the trees. The soil was great around those trees.

It’s supposed to be a decent lumber as well.

Who knew?