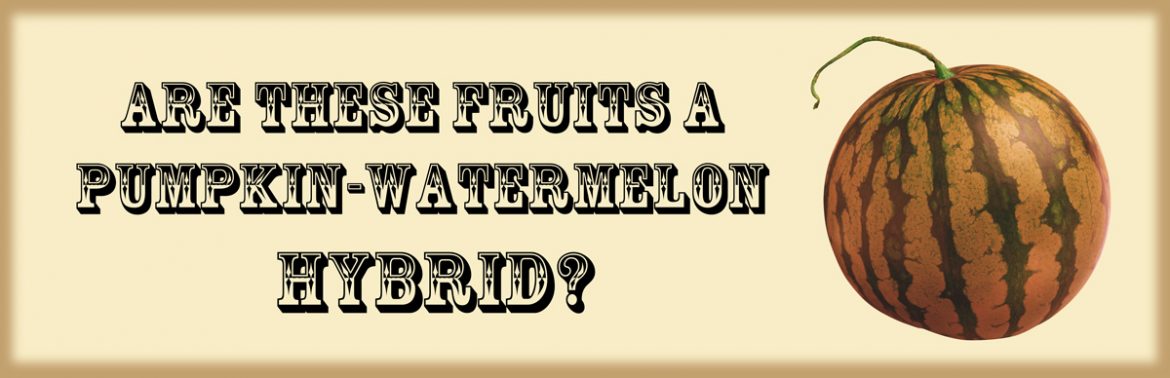

In yesterday’s post on garden experiments, Shane Arthur Swing commented on a possible watermelon pumpkin cross he may have created.

I asked if he’d let me know how it happened and share a photo. He graciously agreed to share more details and sent me both a picture and a write-up on his suspected watermelon pumpkin hybrid.

A Watermelon Pumpkin Cross?

Shane Arthur Swing’s story:

I’ve been gardening in Maryland for about six years now. The first few years were experimentation and learning new plants to grow and new methods to try.

So, about four years ago, I didn’t know any better not to try and cross-pollinate some pumpkins and watermelons I was growing next to each other in separate raised beds. I’d rub the male flowers on the female flowers of both onto each other.

So, the result is visible in the picture – pumpkin-watermelon Frankensteins.

These perfectly ordinary children are completely unaware of the taxonomical abominations that might be unleashed if these watermelon pumpkins were allowed to spread.

Not until this year did I read that doing so was impossible since they aren’t in the same family — I had to dig up the picture from an older computer I knew I had the picture on.

I’d like someone to tell me how in the heck this happened. When I opened up these things, the flesh was more orange-ish than red and had the fibrous texture that pumpkin flesh had but was a bit softer. It was sweet tasting, but not as sweet as regular watermelon if I remember correctly.

I didn’t save any seeds because, back then, I didn’t know this was impossible, and I’d rather just grow individual plants, not mixes.

Is this Possible?

My Verdict

Some strange things have happened via cross-species hybridization and I really want to believe in a jump like this.

That said, upon further consideration of this strange case, my understanding of plant breeding leads me to think it’s impossible for the genes to have obviously effected the look of the pumpkins the first year.

Why is that?

A pumpkin x watermelon would not become evident until the seeds were planted, since the ovary (the fruit) is a product of the mother plant. The plant donating pollen would give its genetics to the seeds and if they were planted and the cross took, you could have plants that bore fruit with attributes of both parents the next season – but this would not be evident until then.

The fruit is a genetic outgrowth of only one parent – and it isn’t the pollen donor. The embryos within the seeds of a pollinated fruit, however, contain traits from both parents.

If you cross-pollinated watermelon and pumpkin and were able to get a successful hybridization, you wouldn’t know it until you planted the seeds the next year.

The best way to tell if you successfully pollinated a bloom – without waiting until the next year’s fruits – would be to do what squash breeders do and tape or tie the female blooms shut the day before they open for the first time. The next morning, you open the blooms and pollinate them just with your male donor flower, then close them again. This ensures that an insect doesn’t sneak in and pollinate the flower when you’re not around.

If the pollination “takes,” the flower will fall and the fruit at its base will grow into maturity. If it doesn’t, the nascent fruit will simply fall off in a few days.

Now – as for whether or not you can hybridize a pumpkin (Cucurbita pepo, C. maxima or C. moschata) and a watermelon (Citrullus lanatus), it is rarely possible to make these types of crosses.

That doesn’t mean it can’t happen. Just that it hasn’t happened and been recorded. Home gardeners are responsible for most of the variety in garden vegetables and fruit we have today, and they’re even responsible for some new species.

Sometimes a cross will happen but all the seeds will be infertile.

Watermelons and pumpkins share the same family Curcurbitaceae but they aren’t all that closely related and they don’t reside in the same genus.

Cross-genus hybrids aren’t impossible, though. Triticale is a cross-genus hybridization between rye and wheat.

Stabilizing a cross of this nature usually takes some work once done, however, as there are plenty of strange things that happen when chromosome counts, etc., get mixed together.

So What Happened With Shane Arthur Swing’s Pumpkins?

Whatever created this abnormal manifestation in these pumpkins must have happened due to a cross in the previous generation or a mutation.

Plant mutations have led to many of our most beloved fruits, flowers and vegetables.

Consider the story of the Navel orange, for instance. One mutation two hundred years ago created one of the most popular oranges in history.

One mutation that led to one branch was later cloned into millions of trees. Photo credit Forest and Kim Starr.

A Presbyterian missionary came across the Navel orange back in 1820 and saved it for posterity. Without him, that branch would be long gone and I wouldn’t be enjoying one of my favorite fruits.

Oranges aside, pushing for crosses and saving mutations is a lot of fun. These pumpkins were likely crossed with another type before Shane planted the first seed in his garden that year – but by all means, keep attempting strange crosses.

If you want to end up with a stable line and your own varieties, I highly recommend Carol Deppe’s book Breed Your Own Vegetable Varieties. It’s fascinating and contains lots of information, including some of her own thoughts on “wide crosses.”

Keep on experimenting. A watermelon pumpkin cross may yet happen.

22 comments

[…] post A Watermelon Pumpkin Cross? appeared first on The Survival […]

I grew watermelons next to pumpkins and got a hybrid. The resulting pumpkin had no ribs, thicker flesh, and smelled exactly like a watermelon on the inside. It also had green splotches on the rind, and the seeds were darker, thinner, and taller than a normal pumpkin seed.

That’s interesting. I never considered that the pumpkin seeds and plants I bought could have been “contaminated” in this fashion prior to me messing with crossing. With this batch, I bought pumpkin seeds online, and I bought the watermelon starters from a local feed store.

Either way, nature is an awesome wonder.

Thanks,

Shane

Yes – or could have just been normal variation. There’s a lot of potential variety, even in generally consistent seed lines. Fascinating stuff any way you roast it.

My dad who does not have a garden had a vine growing in his front yard this year where he has lived for 4 years, We waited to see what it could be. It was round and had the typical green and light green stripes on the outside. We let it grow until the first frost and then he cut the fruit off. It looked just like watermelon on the outside and had a whitish small rind on the inside but the core looked just like pumpkin. I tasted it raw and it sort of tasted like pumpkin so I suggested making a pumpkin pie out of it so he did and it was delicious.

Who knows what it was or how it all happened! But it was fun waiting to see what it was.

The most interesting cross I’ve had in my own garden was from first year seeds straight from the seed pack I believe they were Johnny’s seeds. I had planted vegetable squash and also butternut squash next to each other probably about 10 feet apart. I had one plant that had vegetable squash (shape) growing on it but it was not totally yellow it was a light brown yellow and the inside flesh was a brownish tinted mostly yellow color. It scraped out in strings like spaghetti squash but it was so weird eating it as we expected no flavor and it tasted exactly like butternut squash. I will never figure that one out either.

Great stories. I get a kick out of “wait and see what it turns into” gardening.

One year we allowed some of the squash seeds that germinated in our compost to ramble around the garden. One of them ended up looking just like an acorn type – but was exactly like a spaghetti squash inside. Boy do I wish I’d saved those seeds.

I had what I believe was a cucumber-cantaloupe cross, many years ago. It was rather nasty, so did not save the seeds. Pumpkins and squash cross all the time, so you never really know what the next year will bring. This year’s pumpkins looked nice, but were stringy and inedible, so I won’t be saving seeds.

davidI left a post on one other thread. im not a computer savy person,so im not sure how to contact you. I live in silver springs,out in the forest. im interested in the velvet beans. I would buy them if possible,but to another survival garden guy,i have some trees you don’t..i think. maybe we can trade.

A few years ago I had good sized watermelon and pumpkin patches. The next year I had some volunteer plants that looked to be watermelons. As the plants grew they produced fruit that looked like watermelons. As they matured they had a little orange tinge to them. Upon harvesting and slicing the fruit had an orangish color and an unusual taste. Without thinking much on the matter I discarded them. I have wished many times I had kept the seeds to see what they produced. My wife and daughter with me had a few laughs as we discussed our waterkins or pumktermelons.

That would have been amazing if it was a true cross. I wonder how many people have missed saving seeds and never seen anything that crazy again?

A few years back I planted pumpkins and watermelons next to each other. I purchased both seeds new from my local garden center. As the year progresses the pumpkins looked like pumpkins but the watermelons looked odd. Upon harvesting the pumpkins were totally normal but the watermelons smelled like pumpkins and had an orangish-pinkish color and a stringy pumpkin-like inside. It seemed as if it was half watermelon – half pumpkin. It tastes gross and we had a good laugh but I never saved seeds as it tasted so bad. I’ve read several articles that say it’s impossible to cross them until the next year but what I had seemed to be a cross to me!

Gotta save those seeds next time – you might have inadvertently made gardening history!

I took store bought seeds planted them side by side and got on the first growth a hybrid pumpkin x watermelon

Why is it supposedly impossible

The species are divergent in chromosome count, for one. Pumpkins have 20 pairs of chromosomes, watermelons 11. It’s a hard cross to make.

If you planted seeds side by side, they wouldn’t be able to cross anyhow, as first one plant would have to pollinate the other. It’s in the second generation that you’d see the cross, if it happened that way somehow. Chances are, your seed was crossed with something before you got it. Did you take any pictures? If you did manage to pull off a cross, the seeds would be worth saving and planting to see if it could be stabilized.

I just pulled the plant up two weeks ago

Your assumptions are false.

Development of the fruit would be affected by seed development; it does not occur in a vacuum; however, the full effect of the cross would not be realized until the seeds were planted and a stable hybrid was obtained.

Also, plants have far greater tolerance to hybridization than animals.

Barriers tend to be more about location, pollinators and timing.

Giant Pumpkin Kavbuz

Oaks cross all the time.

A Watermelon Pumpkin Cross? | The Survival Gardener

[…]If you spend slightly extra for a properly made knife, you’ll have a knife to pass all the way down to future generations.[…]

I know it’s an old post, but I recently planted squash and watermelon side by side, and one of the squash’s vines has a normal fruit in it, and a couple feet apart one that seems to have watermelon skin at the same size and ripeness stage. I have pictures if you’d like to see, can’t wait to harvest to see what it looks like inside!

I’ve done it before where all my watermelons tasted like pumpkin. And once I did it with cantaloupe and all my cantaloupe tasted like pumpkin. I grew the seeds right next to each other about an inch apart.

[…] to The Survival Gardener, pumpkins and watermelons do belong in the same Cucurbitaceae family, but they aren’t closely […]

I know I have a watermelon pumpkin cross and have the photos to show.

Comments are closed.